#465: A Viral Article I Disliked

My thoughts on The Atlantic’s article on reading that everyone’s been telling me about

Dear Readers,

Let’s try something new this week. I’m going to share with you a viral article that was published in The Atlantic. Then I’m going to tell you why I thought it was terrible.

Never before have I featured an article that I disliked. But I just can’t resist. First of all, several of you reached out and asked me what I thought. Also, I feel like it’s my duty to prepare you in case this piece comes up in conversation. (Which I believe it inevitably will, if it hasn’t already.)

🎙️ But first: I want to make sure you’re warmly invited to this month’s article discussion.

We’ll be discussing “The Sextortion of Teenage Boys,” by Olivia Carville (gift link). I highly recommend it if you care about young people and worry about their safety online. Read my blurb and listen to my interview with Ms. Carville (she’s a Kiwi!) in last week’s issue. Then, if you’re interested, sign up for our gathering on Oct. 27.

One last thing: A big shoutout to loyal reader and paid subscriber Daniel for pointing this article in my direction.

⭐️ All right, are you ready to rumble? Let’s get into it — first with my blurb of this week’s article selection, followed by my thoughts about the piece.

The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books

Rose Horowitch knows the ins and outs of elite schools. She graduated from Yale University last year. Before that, she graduated from Phillips Exeter Academy.

Somewhere along the way, Ms. Horowitch got to thinking that something sinister had cast a pall on the otherwise hallowed halls of our country’s most prestigious colleges.

That sinister thing, you ask? The students were no longer doing the reading.

Concerned, Ms. Horowitch interviewed 33 university professors who felt the same way. Twenty years ago, one professor said, students had no problem completing Crime and Punishment. Now they scoff at the idea of such a thing. Before, they habitually read 200 pages a week. Now, said another professor, a 14-line Shakespearean sonnet stumps them. What’s happening?

Ms. Horowitch shares many theories for this trend, among them:

Smartphones (of course)

High school teachers no longer assign full-length books

Standardized tests don’t require students to understand novels

College is more transactional now (see Issue #462), and students are in it for the money, not for a degree in the humanities

No matter the reason, Ms. Horowitch is worried. What does this mean about the future of scholarship? she asks. Does this portend the end of empathy, the demise of the appreciation of the human condition? Will anyone ever again read the totality of Moby-Dick or The Iliad?

By Rose Horowitch • The Atlantic Monthly • 9 min • Gift Link

💬 My Thoughts (Or: Why this article made me so mad.)

Before diving in, let’s first discuss my biases:

My entire career, I’ve worked in non-elite public high schools, mostly in San Francisco and Oakland. Out of the 1,500 students I taught, maybe eight of them went to Ivy Plus schools. (However: I graduated from two elite colleges.)

I know a little bit about reading instruction. I taught English for a long time, I lead a reading non-profit, I’ve interviewed Emily Hanford (the Science of Reading person), and obviously, I read a lot for Article Club. This is to say: Maybe this article rubbed me in the wrong way, and I’m being defensive.

OK, with those caveats out of the way, it’s finally time for me to share why this article bothered me so much. (If you want an inside look, feel free to read my annotations as you follow along.) Here are a few reasons:

1️⃣ Ms. Horowitch makes wavering, imprecise claims

The first rule of argumentation is that it’s best to develop claims that stand strong. When they hedge, or move around, your reader is going to stress out, and begin to doubt you — as I did.

In this piece, in which I think Ms. Horowitch wants to argue that elite college students are reading less than they used to (which would have been fine), here are some of the claims she makes:

Elite college students “can’t read books.” (Later on, she says they can.)

“It’s not that they don’t want to do the reading. It’s that they don’t know how.” (Later on, she says they do know how.)

“They’re less able to persist through a challenging text than they used to be.” (So is it skill, or stamina?)

“Students now seem bewildered by the thought of finishing multiple books a semester.” (Or is it psychological?)

In other words, I got lost early on in the piece — mostly because Ms. Horowitch began with a robust, controversial claim — only to weave and shift quickly afterward, leaving me confused.

2️⃣ This piece includes scanty or imprecise evidence

Unless it’s a personal essay (where your lived experiences are your evidence), I look closely at an author’s evidence as they make an argument. You have to have sufficient evidence, and your evidence actually has to back up your point.

Unfortunately, Ms. Horowitch doesn’t do well here. Her biggest problem is that she is trying to prove that elite college students have trouble reading books, but instead of asking them, or sharing some other metric of reading woes, Ms. Horowitch instead interviews professors, asking them about their frustrated (or nostalgic) feelings. To prove the bold claim that high school teachers no longer assign whole books, Ms. Horowitch includes the story of one professor who said he once had a student who told him so. Anecdotes aren’t sufficient, which Ms. Horowitch seems to concede in the middle of her piece, when she writes, “No comprehensive data exist on this trend.” In other words, it seems like her claims are based on professors’ vibes.

There are also problems of imprecision of evidence. To substantiate a claim that high schools are not assigning whole books, for example, Ms. Horowitch cites an EdWeek Research Center survey of 300 third-to-eighth grade educators. In case that piece of evidence isn’t sufficient (it’s not), Ms. Horowitch doubles down, recalling that her elite high school English teacher assigned only one Jane Austen novel in a course focusing on Jane Austen. It makes a good story, sure, and causes a reaction in the reader, but I’m not sure it proves any substantive point.

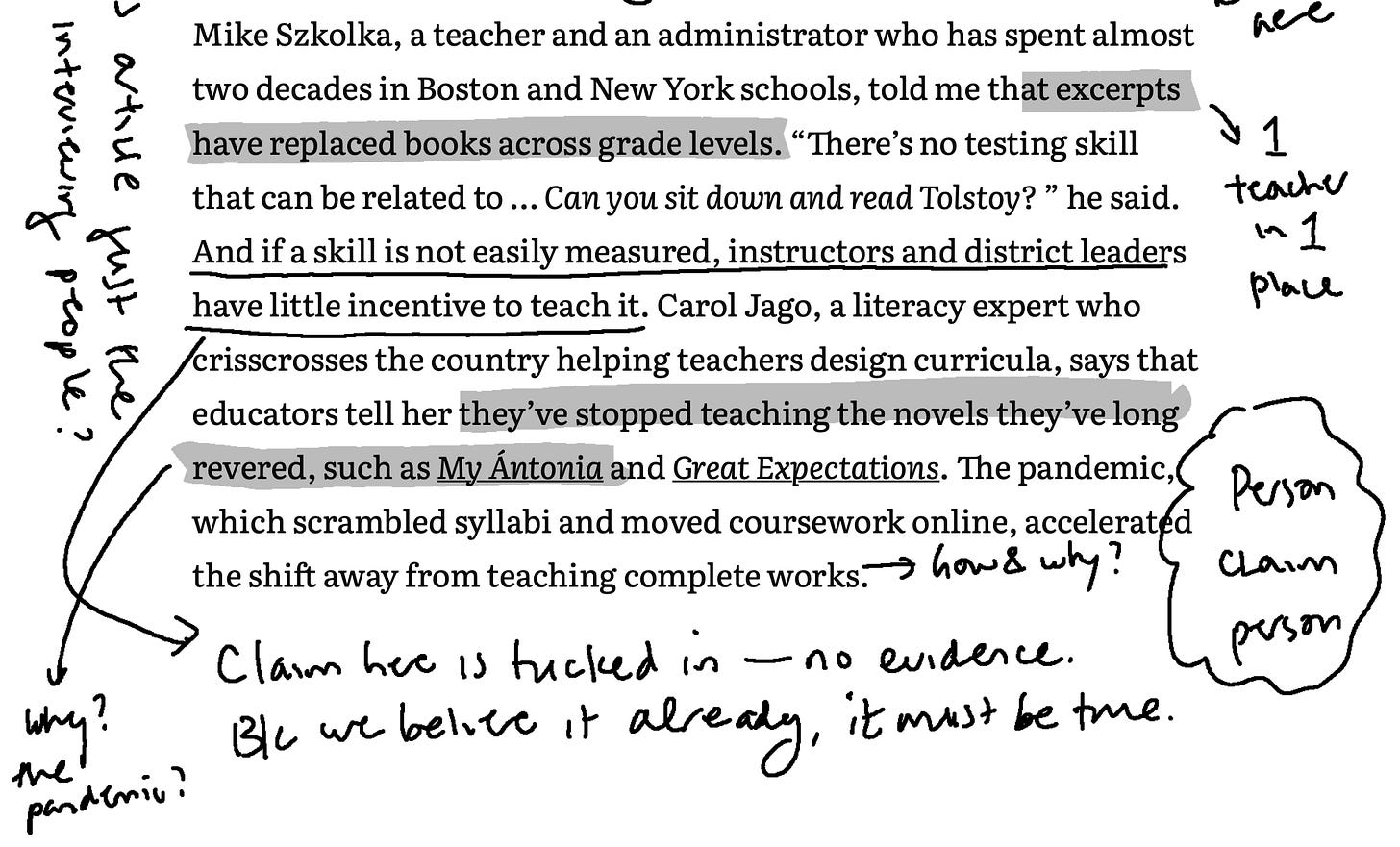

One last tactic Ms. Horowitch employs, which is an advanced sleight of hand, is to liberally quote experts while interspersing related yet unsubstantiated claims. Here’s an example, which I call “person-claim-person-claim”:

Do you see what Ms. Horowitch does here? She begins this paragraph with a veteran teacher decrying that there’s not enough Tolstoy in the curriculum. He suggests standardized tests are the culprit. Ms. Horowitch adds to this idea, introducing a new claim about teacher incentives. Instead of exploring this possible connection, the author instead pivots to a famous literacy expert, whose statement may or may not be related to standardized testing. We can’t be sure, because Ms. Horowitch keeps moving ahead, ending the paragraph with an unsubstantiated claim about how the pandemic made everything worse.

All of this is to say: I’m not buying it.

3️⃣ Is this a problem in the first place, or just snootiness?

The Atlantic loves to publish articles about the fall of education, written by authors who graduated from elite schools or currently teach in them (example). I’m not convinced that kids at Columbia not reading as much as they used to is actually a problem that needs to be immediately solved.

But because I’m an educator, and passionate about reading, I’m willing to play along, especially when a piece includes reading heavyweights like Carol Jago, Daniel Willingham, and Maryanne Wolf. Too bad these thoughtful researchers appear alongside this incredibly snooty, classist (and racist, I think) paragraph:

Yes, out of nowhere, Ms. Horowitch compares elite college students with their peers who attend less-selective colleges. It is clear, she writes, that non-elite students have skill gaps, while elite students obviously do not. And then, after that throwaway line, Ms. Horowitch forgets any additional mention of our country’s significant reading problems — for example, how our 12th graders’ skills have declined over time. Certainly there’s no student at Columbia who struggles with reading, she suggests. it’s just their “attention” and “ambition,” poor things.

Maybe it’s as simple as this: There should be a rule that if you’re going to write about reading, you should know about reading. How about that?

💬 Your Turn: What do you think?

Now that I’ve shared my views, what’s your perspective? I’d love to hear your thoughts and get a conversation going in the comments. You can write about the article, or my opinion on the article. Do you agree or disagree with the author’s ultimate claim, “To understand the human condition, and to appreciate humankind’s greatest achievements, you still need to read The Iliad — all of it”?

In typical Article Club fashon, be sure to be kind and thoughtful!

Thank you for reading this week’s issue. Hope you liked it. 😀

To our 5 new subscribers — including Dave, Gurur, and Og’abek — I hope you find the newsletter a solid addition to your email inbox. Welcome to Article Club. Make yourself at home.

If you appreciate the articles, value our discussions, and in general have come to trust that Article Club will have better things for you to read than your current habit of scrolling the Internet for hours on end, please consider a paid subscription. I am very appreciative of Micki, our latest paid subscriber. Thank you!

If subscribing is not your thing, don’t despair: There are other ways you can support this newsletter. Recommend the newsletter to a friend (thanks Melanie!), leave a comment, buy me a coffee, or send me an email. I’d love to hear from you.

On the other hand, if you no longer want to receive this newsletter, please feel free to unsubscribe below. See you next Thursday at 9:10 am PT.

Here’s a masterful roast of Horowitch’s Atlantic essay from Rochester University’s Three Percent, Mark. It’s a hoot.

https://www.rochester.edu/College/translation/threepercent/2024/10/07/rose-horowitch-and-the-obsession-with-belief-over-empiricism/#:~:text=The%20Atlantic%20has%20been%20referred,Affairs%20went%20easy%20on%20them.

Glad you brought this up! I felt the article, even the summary when I saw it on Instagram, screamed "kids these days! get off my lawn!" It is being shared as if it were a study. 33 hand-picked opinions does not a study make. I even had a relative who is a high school English teacher share it in agreement, which surprised me. MY anecdotal evidence as a non-teacher non-parent is that all my nieces and nephews constantly are reading books. So, maybe I should write an article about that! Haha. Perhaps the next think piece can be about the infinitesimally short attention spans and lack of literacy that the typical adult has...